- Home

- Beatrice Masini

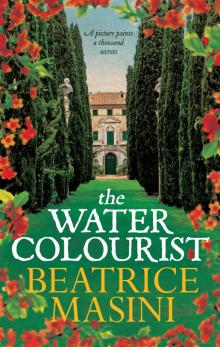

The Watercolourist Page 5

The Watercolourist Read online

Page 5

Her son and daughter-in-law laugh. Bianca blushes. She hates being the centre of attention but smiles nonetheless. Sly old lady. She certainly knows how to lead a conversation. It is an art that Bianca still has not mastered, and perhaps never will. It is easy to imagine Donna Clara perfectly at ease in a Paris salon, surrounded by beautiful minds, an elegant and respectable man at her side listening to her playful quips complacently. What sort of man was Conte Carlo, her lover? Why is there not even one portrait of him in the entire home? After all, the house was originally his. The older woman inherited it when he died. Perhaps they are hidden away like relics in the secrecy of her private chambers, or inside the locket around her neck, shut away like prisoners within her bosom . . .

‘Miss Bianca? Miss Bianca? Where did you disappear to?’ It is Innes. ‘Our little dreamer,’ he jokes.

‘I wasn’t dreaming. I was just thinking. Is it not allowed?’ she answers, thrown by his intimate manner.

‘If it takes you away from us, then no, my dear, it isn’t. You must remain here. Propriety imposes this on us.’

Bianca looks at Innes in confusion. It’s something Donna Clara would say. She wonders whether Innes is mocking the mistress.

Don Titta intervenes.

‘Personally, I don’t mind. You are free to go where your heart and mind take you, on the condition that you will come back and join us here on earth occasionally. I understand.’

‘Of course you do! You love to visit that secret place that Miss Bianca disappears to, isn’t that right?’ laughs Donna Julie. ‘Far away from here, from us, from our incessant voices, the buzzing disturbance that we are.’

‘But I love my crazy bees, too, and you know it,’ he says, smiling. ‘And love has the right to disturb me whenever it feels like it.’

He said, ‘Whenever it feels like it.’ He should have said, ‘Whenever I feel like it.’ If she hadn’t heard him with her own ears and seen how pleasant and serene he is, Bianca would never have identified this as the man who walks indifferently past his children while they call out for his attention, eager to show him their recently finished drawings. At other times, he shuts himself in his studio for days, refusing trays of food placed at the door. He won’t even open the window of his study. Donna Clara paces beneath it, looking up, waiting for a nod, for some sign of life. Sometimes the poet has nightmares and calls out during his sleep. She has heard him. It isn’t a dog or a local drunk, Minna tells her. It is him.

‘He does that sometimes when he is writing,’ she says.

Bianca begins to understand why the children are always so insecure in front of him. They are stuck between shyness and the urge to reclaim his other, kinder side, the side that sends the gardener to plough the grounds at the confines of the estate into five parcels so that each child can have their own garden. Each area is labelled with a wooden tag and the children have their own set of miniature hoes and spades and tiny bags of seeds to plant. Don Titta is a complicated man, this much is certain. One moment he is there and the next he is gone. He isolates himself for weeks so that he can pursue, capture and tame his muses. And then, all of a sudden, he resurfaces: a pale and serene convalescent. He becomes that other self then, the man who joyfully goes out on a limb for everyone. The man who kneels down next to Pietro and Enrico, fascinated, as they watch a watermill churn over the brook. Who admires the girls as they dance to the rhythm of Pia’s drum, smiling so sweetly he looks almost foolish.

If their father is either fully present or fully absent, their mother, delicate and devout Donna Julie, is a constant source of love. It bubbles up from deep inside her. Precisely because of her uninterrupted presence, though, she runs the risk of going unnoticed. It is her daily devotion that watches over the children’s health and their metamorphoses, providing woolly sweaters, poultices, decoctions or mush as needed. She offers them all the nurturing that they require. But the children, observes Bianca, are no longer so young that they need such doting attention. They are at a point when they desire something else: games, friendships, stories and laughter. Kisses and hugs are excessive. They reciprocate with swift pecks on the cheek and then wriggle free, the same way they do from unwanted scarves and sweaters. Although when Donna Clara offers herself to them, they greedily take everything they can get their hands on. They adore Innes too, like little puppies. He is the only one who can get respect from the two boys, and the girls love him unconditionally – maybe because he is as tall as their father but not as distant; maybe because he swings them around him as if on a wonderful carousel ride.

One day, through an open window, Bianca hears Nanny complaining.

‘Oh, that Miss Bianca . . . she’s going to take him from me. I know it. And she doesn’t even speak French!’

Bianca is astounded: Nanny is revealing her feelings to a maid! And probably a smart one like Pia. She wonders what would happen if she were to make a dramatic entrance, draw back the curtains, as in a Goldoni comedy, and say, ‘You’re wrong, mademoiselle. Innes is all yours. I’m looking elsewhere.’ The foolish girl would be at peace but it might also kindle the fires of her hope, which is a mere illusion. She ought to realize on her own that Innes is unattainable. Maybe she wants to delude herself. Maybe it makes this house, her prison, more tolerable. But the children will grow up, Nanny will have to find another home, and by then Innes will surely be far away. He doesn’t strike Bianca as the type to stay fixed in one spot for very long. Not here, anyway. He is a dreamer. And the dreams will ultimately carry him away.

She stands very still, thinking and listening. Pia, surprisingly, comes to Bianca’s defence.

‘What are you talking about? Miss Bianca isn’t a bad person . . .’

Bianca wishes that she could transform herself into a beautiful statuette. No one would notice her; she would simply be an ornament, an ornament preferable to the one she feels she already is. Words would simply slide off her smooth skin. She recalls a French story her father used to tell, the one about an ancient statue, a Venus in a garden somewhere, that fell in love with a young man. Every night the statue would visit him, leaving mysterious traces of dirt in the hallways of the villa. To prevent him from marrying his flesh-and-blood fiancée, she held him so tightly that she killed him. Even statues have a soul. The advantage is that no one knows it, and they can conceal or reveal them as they please.

As she turns the corner of the house, Innes comes towards her, as though he has been waiting for her behind the bushes.

‘And where are you off to, Miss Bianca? To explore the wild moors?’

Bianca turns to look behind her. If she has seen this exchange, Nanny will have fainted, her suspicions all but confirmed.

‘I was just going to walk down to the fields, where it is a bit less wild,’ she says with a smile.

They start walking together. He has to slow down and she has to quicken her pace. Once their initial differences are dealt with and the doses of irony are measured out and understood, Bianca realizes that not only does she enjoy Innes’s company, but she also doesn’t care what Nanny thinks.

‘Were you referring earlier, perhaps, to our employer’s wild habits?’ he says. They exchange a smile of understanding, but he then becomes serious. ‘He is a great man, you know. I feel fortunate to work for him. And so should you. The bourgeoisie of the Po Valley, the landed gentry, the aristocrats who inhabit these spaces that exist somewhere between land and sky, are rarely so enlightened. More often than not they are simply satisfied with conforming to the landscape.’ And then Innes changes both the subject and his expression. ‘I have something for you. It has just come from London, where it seems to be a great hit. It’s a romance novel and I am sure you will appreciate it.’

‘Don’t you want to read it first?’ Bianca asks, trying to suppress her curiosity.

‘I’ve already read it. My nights are inhabited by books. It’s the only benefit of having insomnia: one has more time to dedicate to passions. I also sleep a little during the day, when it’s n

ap time for the children.’

She notices his paleness. His eyes are more deeply set than usual. In the vivid daylight, barely screened by the leafy treetops, she notices, too, a vertical line that runs from the corner of his eye down his cheek. It looks like a scar from a duel but is merely a crease of age, perhaps a distinctive sign, a message saying this is the spirit at work. Bianca has begun to suspect – and in this she is correct – that Innes is a revolutionary. Merely thinking of this word sends chills running down her spine. It evokes torture, chains, prisons, heads rolling in pools of blood. His frequent visits to the city surely serve a duplicitous purpose. And the role of tutor in a noble and respectable family is a wonderful cover.

Bianca senses that even the master of the house is involved. Their partnership in these matters explains many things: Don Titta’s secrecy and his frequent trips to the city residence (which she imagines as being dusty and decaying, in ruins, given the fact that none of the women ever want to go) with the excuse of researching the novel he has been writing for the past ten years. The risk of course is even greater for Don Titta than for Innes. He is the poet, loved and pampered by all for the person he appears to be: an elegant, charming seeker of words. Bianca, who is familiar with his work, finds his poems pleasing but wan. She doesn’t see great passion in his verses but rather delicate sentiment, idylls, still-life depictions of an illuminated life, a life which does not truly exist.

Perhaps at heart he is a collector – that would explain why he is driven to commission portraits of his flowers and plants as though they are people. But what if, under that Arcimboldo of petals, strange herbs, exotic fruits and foliage, there is a different man, a man filled with strong ideas, waiting for the right moment to reveal his true identity to the rest of the world?

His novel. The revolution. Perhaps he is writing a novel about the revolution. Bianca feels only a detached curiosity about these matters. She is aware that they are important, that it is an issue of rights being denied, and that the insurgents operate through contempt, secrecy and violence. Apparently, there is no other way to protest and change the direction of things. There will be blood. It is inevitable.

Bianca, though, feels engaged in her own transformation. It has turned her world upside down and set her apart from everyone else. She tries to imagine the new and daring map of the world to come. She feels like a seamstress working on a corner of an enormous tablecloth: she has her portion to bring to completion and she simply fills it with stitches and then unstitches them, little understanding how that same motif will multiply and echo across the cloth.

The book that Innes lends her takes her breath away. It keeps her awake at night; it steals away her common sense, and creates a confused knot of sensations inside her. It is entitled Ponden Kirk and focuses on a desperate and impossible love story, on injustice, and on ghosts that inhabit a desolate moor near the sea. She can imagine Tamsin’s small hand, white against the black of night, scratching at the windowpane. Or perhaps it is only a branch. That hand, the description of those curls and amber eyes, eyes that are common here but rare in the north, takes hold of Bianca’s heart. She feels the darkness that surrounds the beloved character of Aidan and feels for him with her innermost soul. It is completely different from Udolpho; Emily is a silly goose in comparison and not worthy of holding Tamsin’s umbrella. Tamsin would hate umbrellas, anyway. Bianca is certain of this. If she ever did own one, she would have snapped it in two in a burst of rage or forgotten it under a hedge, torn it with carelessness or allowed it to be swept away by the wind. All of a sudden, everything Bianca has read that year is discarded in favour of this novel.

Innes smiles and tries to answer Bianca’s insistent questions about the writer.

‘The author’s name is D. Lyly, with a “y”. That’s all I know.’

‘No first name?’

‘No first name. I think it must be a pseudonym. It has to be a woman.’

‘Another Ann Radcliffe?’

‘Why not, my dear?’

‘I tremble for her.’

‘You tremble?’

‘Out of repressed envy.’

D. Lyly, Delilah, Dalila: a woman of deceit. Deceit in order to exist. To write. In comparison, Bianca’s pencils, charcoals, all the accoutrements of her drawing, seem as bland as the oatmeal that her mother served her at breakfast while her brothers enjoyed pumpernickel bread and sausages. Her flowers are mawkish in their light green and gold frames. The leaves in her sketches have been dead for an age. Everything she does is so graciously finished – and so useless. Life looks so much better alive than when it is drawn on paper. When it is written about, on the other hand, life becomes stronger, colourful, more vital. And what is more, writing comes to life each time you read it. A leaf drawn on a piece of paper does not. When a leaf dies, you have to wait for spring to be able to see it again, and it will never be the same leaf it once was.

Bianca is curious. She wants to find out more about this mysterious Lyly, who is very possibly a woman. Who knows what depths and peaks of passion she has experienced in order to be able to render them so miraculously well on paper? Maybe she is like her character Tamsin, both impulsive and obstinate, reaching out for everything she wants against all obstacles. She is never defeated, only by death. But no, not even that can stop her . . .

‘The author is most likely a middle-aged man with gout,’ observes Innes playfully. ‘He spends every day at the club and has never travelled further than Hampstead.’

‘You like teasing me,’ Bianca protests.

‘You should write, if you think you might enjoy it,’ says Innes, both indulgently and in all seriousness. They are walking together in the rain as if they are in England. They cross paths with servants and peasants who look at them askance. It is one thing to have to get wet, but another to do it on purpose, dragging one’s skirt through the high grass in a strange pique. ‘Write. Try it out. No one is stopping you. I know that your true talent is drawing, but it needs to find its right course. Don’t tell me you’re only interested in herbals. That’s just the surface.’

And so, with that challenge, Bianca gives writing a go. On a stormy night, illuminated by candlelight, she starts a fictitious diary. It doesn’t come easily to her. She gives herself a false name, rolling it around in her mouth as though it is a strange sweet, unsure whether to keep sucking on it or spit it out. She writes out the false name three, five, ten times, tilting her flourishes here and there. Finally, she recounts her experience travelling from Calais to Dover. She leaves out the more distressing details, the jumbling of innards, and favours a more romantic sketch: two mysterious characters in wind-swept capes, the moon peeking out from behind the clouds . . . She rereads it. It has all been said before. She gives it another go, adding the innards and their by-products. The effect makes her shiver. There is action and atmosphere, but it all feels shallow. She cannot find the right words. She ends up with blackened fingers and torn-up pages. It is better to read than to write, she thinks. And what’s more, it’s easier.

She gets into bed to read the novel, and is immediately reunited with Aidan; she locks that silly Tamsin in the storeroom, ignores her small fists pounding on the door, steals her cape and effortlessly clambers up on a horse behind her hero. Together they ride off bareback, the beast trembling beneath her thighs, her arms gripping his waist tightly. He, too, trembles with the fury of the gallop. It is pouring with rain, and the moon is shining . . .

The moon is always present, she reflects as she closes the book, thunder sounding far off in the distance. She looks out at her own moon through the distorting glass pane of her window, and thinks it looks like a fried egg. It is always with us, she thinks, even when we don’t see it. And we need it like we need the sun. It’s the other side of the coin, the splinter of darkness we carry with us, wedged into our hearts. She sighs and picks up a pencil and begins to draw. She draws the fried egg in the sky, the profile of a sycamore, a star like a tiny kiss of light. This much she can

do. And this she will continue to do.

The feast day of San Giovanni is a small but important tradition in the household. Friends from the city visit on the way to their own summer retreats in the countryside in a kind of farewell until October. It is an opportunity to show off the estate and prove that some things never change. Bianca learns about the feast only during the commotion of the preparations, from the servants’ incomprehensible, fractured sentences; from the contrasting expressions of Don Titta and his mother, who is reassured by the agitation and shouts orders left and right like a captain from the bridge. Don Titta confirms his own place by retreating into his chambers. When his opinion is needed about the menu, the flowers or the music, he raises his eyes to the sky and purses his lips as though to hold back any impertinence.

St John’s Wort is in bloom during the period of the feast. Bianca has an idea, voices it, and it is approved. Her role is to prepare dozens of boutonnières: a cluster of the little yellow flowers bound in ivy shoots. She sends out troops of children to search for the smallest ivy – only the ends of the branches, about this long, no more than that, be careful not to cut yourselves, don’t run with scissors in your hand, and so on. Despite Nanny’s worrying and the devastating pruning job, the mission is completed. When the ladies and gentlemen arrive, the children present them with these boutonnières, sprayed with water to appear fresh, from two trays in the foyer. The guests, of course, remark on the children’s growth before pinning the gifts to their chests.

‘Oh, how big you’ve got, Giulietta. You look like a young lady.’

‘And is this Enrico? He looks like his grandmother. What a beautiful boy.’

Nanny watches the children from behind a pillar, ready to sweep up her prey as soon as the last guests make their entrance. The gates close, keeping out the local peasants, who are travelling to their own festival in the village piazza, and who stop to watch the arrivals. They hang onto the gate and spy for a while on the gentlefolk and their painted carriages, neatly assembled along the gravel drive like a collection of exotic insects.

The Watercolourist

The Watercolourist