- Home

- Beatrice Masini

The Watercolourist Page 4

The Watercolourist Read online

Page 4

‘Donna Clara, you have no use for miracle waters. Here at Brusuglio lies the fountain of youth. I am certain it’s somewhere here on the estate and you’re keeping it secret while I wander high and low to find it!’

Innes speaks Italian with no trace of an English accent. Bianca finds out later that his mother is Italian, too. He switches immediately to his paternal language when talking to the children and when Donna Clara introduces Bianca to him.

‘And here is Miss Bianca, with whom you will have a lot in common, I’m sure. But you must speak our language together from time to time. We don’t want any conspirators in the house!’

And with this, the children take hold of him and drag him away to see a brood of ducklings. They are halfway down the path when the master of the house leans out the top-floor window.

‘Innes! Finally!’

The Englishman turns around with a smile, unable to free himself from the grasp of the little ones.

‘My friend, I’ve just returned and already I’m being held captive!’

‘I can see that,’ replies Don Titta. ‘As soon as you manage to escape from that tribe of savages, you will find me in my study.’

Innes smiles in agreement before letting himself be dragged off once more.

His full name is Stuart Aaron James Innes. He studied at Oxford before the collapse of his family business – shipping and trade in the Indies – forced him into another, truer, profession. His natural passion for travel and a strong desire to avoid ridicule from his peers led him to leave England. This is his third appointment as tutor. He has already been to Paris and the Savoy region before being stranded – his words – in the Milanese countryside. He tells her all this in their common language, standing together beneath the portico, waiting for dinner to be announced. Darkness falls sluggishly, little by little, first swallowing up the forest in the distance and then the confines of the great lawn. His hair is curly and somewhat long. He constantly brushes it away from his face in an unintentional, almost feminine, gesture. His eyes are of a piercing blue, strong yet distant. He wears a thin, precise moustache and has a hint of a beard that gives him a medieval air. His elegance is sober and neat. His frock coat, though on its last legs, is impeccably pressed and beautifully cut. After telling her his story Innes is quiet for a long moment, taking in the view of the estate, which is so beautiful in this, its bluest hour.

‘I am pleased that you are here,’ he says. ‘I feel like your presence will make my exile more tolerable.’

Bianca thinks this comment rather dramatic and somewhat forward, and hides herself behind a silence that he interprets as shyness. And perhaps this is for the best.

At the dinner table that evening, he and Don Titta are the only ones to talk. They speak of another poet, an Englishman and old acquaintance of Innes’s, who lives somewhere between Venice and the countryside. The man in question keeps his horses at the Lido so that he can ride along the beach, where sea meets sky. They speak, too, of a mutual friend, Jacopo, who died in uncertain and mysterious circumstances.

At one point, Donna Clara throws her napkin down on the table in irritation.

‘Can’t we talk about something that is of interest to us, too?’

Her son glances over at her with calculated slowness.

‘I am surprised you do not find any of this interesting. It concerns all of us.’

Bianca would like to know what he means and struggles to find the way to phrase her question, but stops when Donna Julie places a delicate hand on her husband’s arm.

‘Your absence has been a burden to your mother. Don’t be surprised if she seeks your full attention at one of the rare times you are at dinner with us.’

There is an exchange of glances between Titta and Innes that reveals a certain tacit understanding.

‘I apologize, Mother dear,’ he says. ‘Sometimes I forget that time passes differently for me than it does for you.’

Satisfied, Donna Clara replies, ‘It’s because we’re women and without you men we’re nothing and we know nothing.’

‘Only if you want it to be so,’ he retorts.

She lets the matter drop and changes the subject, moving on to a discussion of silkworms and the experiments Ruffini is conducting in Magenta.

‘Perhaps, we can go and visit. What do you think?’

And just like that, the whole family is back together, and life in the villa regains its pleasant routines. The poet joins them more frequently for dinner since Innes has returned; it is clear that he appreciates regular male company. Unlike the governess (whom Bianca starts calling Nanny, quickly followed by everyone else), who is encouraged to disappear after meals with the children, both Innes and Bianca remain seated at the table. Their opinions, it seems, are both desired and appreciated. They speak about everything, from the astronomical cost of seeds from Holland to the washerwoman’s marriage and the secret societies of illuminati in Milan.

Innes, who goes to the city twice a week to attend gatherings of a group of fellow countrymen living abroad, always returns with news that excites something more than a polite curiosity in the poet. And just like that, the two of them will begin a discussion that often uses the word ‘fatherland’. The term explodes like a firecracker in the centre of the table. Mother and daughter-in-law will look at each other worriedly. Donna Clara will abruptly interrupt with some mindless topic of discussion: Enrico’s latest stomach ache, the umpteenth doctor’s visit on account of Giulietta’s fever, or the pestilence of rabbits. Bianca, who has seen and heard more than would generally have been allowed for a woman of her age and status, and who has also learned a great deal from her father, is still not quite the free and complete creature that she desires to be. So she remains silent, hushed by good sense, and yet impatient and eager to say something bold and intelligent that will make these two men look at her in admiration and realize that women have minds too. But no, she says nothing. She doesn’t have a legacy of ideas; her best tutor left her too soon. Bianca is like a half-finished marionette, a prisoner carved out of wood. But she may not fully know it. If you could see me now, Father, she thinks, how I take in every new word, every modern sentence in an attempt to understand how the world is changing, just as you wanted me to . . . If he could see her, he would surely be troubled.

She overhears voices while walking past an open French window.

‘She’s beautiful but glacial too. Her name suits her. White is a frigid colour. She’s like snow and ice and wind and storm. And hail.’

Someone chuckles.

‘She doesn’t show off, she keeps to herself. You can’t expect her to mingle with us servants. She’s an artist, she is.’

‘Sure, an artist,’ another voice speaks sarcastically. ‘She’s a servant, but one that gets a nice big bag of coins. All we get is soup, these rags on our back, a cot up in the attic and a kick in the arse!’

This brings laughter all round.

She wants to walk away but stays there, needing to hear more. She tries to shrug the comments off, but finds she can’t. She just feels angry and upset. What irritates her most though is their accent, how they stretch out their ‘e’ sounds, as if they are made of rubber. And at the same time, behind her back, the servants laugh at the way she pronounces her own ‘e’ – quick and closed – and at her clenched double consonants. Deep down she knows they aren’t malicious, though. They are just suspicious of anything new, like all country folk.

On another day a further snippet of conversation comes from another window, painting another portrait of Bianca.

‘She’s not talkative, and as far as conversation goes, she’s as bristly as a porcupine, but she does draw like an angel. Or a devil! Anyway, it’s the same difference,’ Donna Clara says to a mysterious listener. And then she presses a finger to her lips and shushes herself, snickering slightly.

Bianca cannot see the gestures that soften the maliciousness of the words, though. She can only hear the pair’s laughter. She walks away, vexed. She

wanted to find out what they thought of her and now she knows.

Since the return of Innes, evenings unfurl predictably. The men talk among themselves. The women sit in silent disapproval, eyeing them, and desperately seeking to change the subject. Bianca listens, watching Innes’s demeanour and her master’s fervour.

‘Do you really think that things can go back to the way they were? I’m sorry, Don Titta, but I think you’re dreaming. The memory of that Italian officer being killed by the mob just because he wore an Austrian uniform is still fresh in their minds.’

‘It was not as if we wanted to kill him! It was an accident. You know how these mobs can be.’

‘Of course. I can’t imagine you, of all people, stabbing a poor disarmed man with an umbrella. But other people have other predilections. Need I remind you of the chef who was roasted at the Tuileries? Or Simon the executioner with blood up to his ankles? Listen to me, thanks to the death of that poor devil, the Austrians will have an easy time slamming their iron fist down on the table. There will be no lenience, not even towards you patricians.’

‘It’s too late to go back to tyranny. The people are tired. Populations are no longer indistinct masses; they want to claim their own identity. And we – we who know, we who understand – must try to act as new men or at least attempt to renew ourselves. Even if this means risking our world.’

‘You should hear yourself, using words like “too late” and “no longer”. You are so absolute, so excessive, my friend. When people have bread for dipping into their soup, calm will return. And we shall stick to fighting our princely battles in the safety of our salons.’

‘What you say is terrible, Innes. Offensive, even. You make me feel guilty for how things are being played out. Though I suppose you are right. If I stay here, I am hiding behind a screen.’

Donna Clara looks up from her embroidery and interrupts the conversation with measured amusement.

‘Ah, the new one is charming, isn’t it? The chinoiserie is exquisite. Donna Crivelli saw it and ordered the exact same one . . .’

It is strange to hear the men speak so openly in front of the women. Usually their more serious discussions – complete with whispers and sudden outbursts – are reserved for the other drawing room and paired with cigars and alcoholic beverages. Bianca follows this exchange attentively but achieves only a vague understanding of it. She knows there is unease in Milan following recent violent acts. Even her journey here, to Brusuglio, risked being postponed. But the waters calmed and she took her uncomfortable carriage ride.

The last time she heard about world events directly was from her father. She no longer has anyone who will explain things to her. Zeno, in his letters, writes only about parties, hunting scores, or young ladies named after flowers.

Now Don Titta frowns at his mother as if he is surprised to see her sitting there, like she is a fly on a glazed cream puff.

‘You know, the Oriental screen, the one we put in the boudoir up in the gallery,’ Donna Clara insists.

‘Indeed, it’s incredibly useful,’ her son observes drily. ‘You never know when a gust of wind will blow in and hurl you across the room like a balloon.’

‘Speaking of that, you know, I read in the Gazzetta that you can take a day trip by hot-air balloon from Morimondo now. You just need to book in advance.’

‘It’s not for me,’ Donna Julie chimes in. ‘I’m not going all the way up there. I’m too scared. If man were born to fly, our Lord would have designed us with wings like birds.’

‘And a beak to peck with,’ little Pietro interjects. Out of place and largely ignored, he chuckles to himself.

‘To fly . . . what a dream,’ Innes adds. ‘We have no idea what feats man is capable of. This is the mystery and the miracle of science, is it not?’

‘I prefer poetry,’ observes Donna Clara. ‘And not just because it provides us with food on our plates and a roof over our head. I’ve always admired it.’ Placing a hand on her heart, she starts to recite:

Je serai sous la terre, et, fantôme sans os,

Par les ombres myrteux je prendrai mon repos.

‘How lovely, Mother dear,’ Don Titta says with a sigh, tossing his napkin onto the table in an act of surrender. ‘Balls, screens and musty rhymes . . . I can’t take this any longer.’

‘Well, taste is taste. Poetry doesn’t have to make us laugh, now, does it?’ objects Donna Clara.

‘Ask our Tommaso what he thinks of poetry when he arrives.’

Donna Clara can’t resist the urge to get in the last word.

‘Wonderful idea, my dear son. I will ask our Tommaso. That boy needs to have his head examined. You know, you are setting a terrible example for young people who aspire to an artistic life. You were good enough to succeed, but art is not meant for all. Let’s just say that not all buns come out perfect.’

‘Interesting. First I am told I am an artist and now I’m a pastry chef.’

‘Well, what difference does it make? You knead with words, you knead with flour. People are as greedy for verses as they are for cream puffs. Luckily!’

Titta and Innes laugh heartily. Donna Clara looks around proudly, to see the impact of her witty remark. Donna Julie and Bianca only smile weakly. To Bianca, the thought of poetry being bought and sold like pastries – verses on a platter to be picked up with two fingers and eaten – disturbs her profoundly. It seems out of place and hateful, and she wonders why Don Titta is laughing.

‘Our Tommaso’ arrives to stay. Tommaso Reda is also a poet. His family wanted him to read law, but he was against the idea and felt summoned to a higher calling. Somewhat of a dreamer, he had even been locked up in prison for several nights on account of his erratic behaviour. Finally, Don Titta offered the boy help – and shelter too – something which angered Tommaso’s father. Donna Clara explains all of this to Bianca without hiding her disapproval.

‘It’s not like his poems are as good as my son’s. In my opinion, he doesn’t even have a voice,’ she says, stressing her words. ‘He’s just a figurine, a gros garçon used to having anything and everything. And Titta, God bless him, took him in like a stray cat only because he pities him. But this isn’t a hotel. Not at all.’

Why the younger poet evokes such compassion in the master escapes Bianca. He is a young man of medium height, elegant and intense, with a worried look in his deep, dark eyes that contrasts with a cockiness stemming from the privileged status into which he has been born. He wanders indifferently about the home in which he is a guest. He has been coming here ever since he was a child, knows the estate inside and out, and everyone knows him. He eats little and drinks a great deal. He sleeps until late and his candle is the last to go out at night. This moderately excessive lifestyle blesses him with a feverish air and a pallor suited to the role he has chosen for himself. Bianca cannot decide if she likes him or not.

‘Nature really does provide us with the most delicious things,’ comments Donna Clara at the table one day. Her son nods in agreement as he enjoys the last glossy grains of rice from his plate.

‘And the most beautiful,’ adds Bianca impulsively.

‘You are absolutely right,’ Donna Julie agrees, looking over at her children all seated in a row.

But Bianca meant something else. She looks out of the French window again and admires the imperfect contours of the poplar trees, their tips like brushes painting the deep blue sky.

Don Titta leans forward.

‘Yes,’ he says, ‘and art is the attempt to imitate the inimitable. There’s something frustrating about that, isn’t there? I obviously speak for myself, Miss Bianca. Perhaps it comes easily to you?’

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ she answers, her mind returning to the table. ‘My aim is more one of interpretation.’

‘Which inevitably means transformation,’ he remarks.

Bianca purses her lips into a smile.

‘Perhaps. But that doesn’t worry me. Mine is purely an attempt.’

‘The advan

tage is that no poppy or anemone will complain about their portrait not looking like them. Or rather, I should say that I’ve never heard them complain,’ Tommaso intervenes, smiling coyly. Bianca ignores him. ‘But, who knows? Maybe they do complain,’ he says, pursuing the fantasy.

‘What? You think flowers can speak?’ intervenes Giulietta, the only child to have followed the conversation, with all the attention possessed of a nine-year-old.

Enrico and Pietro chuckle.

‘And you can hear them,’ Enrico says, making a circular gesture with his index finger near his temple.

‘I’m not crazy,’ retorts Giulietta, offended, ‘but I do listen!’

‘And you’re right to do so. Of course flowers can speak,’ intervenes Bianca. ‘But they have such tiny, soft voices that all the other noises drown them out. They are born, they live, and they die; why shouldn’t they be able to speak?’

‘This conversation is nonsense,’ says Donna Clara, who has a fondness for eccentricities but only those she champions. ‘Have you ever considered painting children’s portraits rather than likenesses of flowers? There’s a business in that.’

‘Yes, indeed,’ intervenes Tommaso, ‘given that everyone is convinced that their child is the most beautiful in the world. Surely you would find clients in Milan. Rich men who marry beautiful women in order to breed well. Men who don’t always get it right the first time, but try and try again . . .’

‘We can help you, if you’d like,’ Donna Clara adds, not picking up the irony of Tommaso’s comment. ‘We know people, I mean.’

‘No, that is not my profession,’ Bianca says firmly.

‘But you are so talented,’ Donna Julie adds.

‘And, anyway, Miss Bianca,’ says Donna Clara with a laugh, ‘if, in the end, you find that painting a convincing, realistic portrait of a child is impossible, you can always create one of your own instead.’

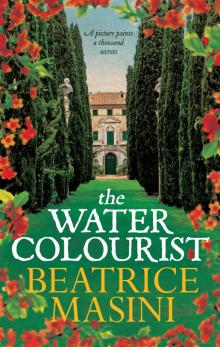

The Watercolourist

The Watercolourist