- Home

- Beatrice Masini

The Watercolourist Page 11

The Watercolourist Read online

Page 11

‘They are our angels,’ she says.

Bernocchi looks up at the sky and then down at his pudding, driving a spoonful into his mouth.

Children as poets and angels? Children are complicated, difficult, often sick, a source of anxiety, frequently whiny, and usually incomprehensible. At least these children are. They have been confused by rules that have often been contradicted with exceptions and turned into new rules. They are different from others and aware of the privilege that is bestowed upon them as their grandmother’s pets, their mother’s stars, and their father’s arrows of hope. They are never simply children. Innes is the only person who approaches them from a different angle: he teases without humiliating; he reignites dormant interests; he knows how to engage and challenge them. He is a natural-born father. Maybe it’s easier to educate other people’s children than it is your own, Bianca thinks to herself, in the same way that it is easy for her to play with children, too. Playing is one thing she can do with ease.

One time Bianca lures them into the kitchen, taking advantage of Donna Clara’s absence, to make a batch of fairy cakes.

‘Sweets for fairies? Really?’ Matilde asks, her face revealing incredulous conviction.

‘They’re called that because they are tiny and delicious and because they are the same ones that fairies have with their tea.’

‘But fairies don’t really exist . . .’

‘You bet they exist; they are this tall’ – Bianca makes a C shape in mid-air with her thumb and index finger – ‘and they have wings.’

‘And they drink tea every day like the English,’ Pietro intervenes drily.

‘Every day,’ Bianca repeats solemnly. ‘But now, enough chitchat. If you used your tongue to mix your dough, it would be perfect.’

‘My tongue? Yuck!’

‘Yes, exactly. Hush and get to work.’

The twenty minutes in the oven feel like an eternity. While waiting, the children listen to her story about how a fairy is born each time a child laughs.

‘So if we laugh they will come?’

‘They will come and will never want to leave.’

‘Never ever ever?’

‘I don’t believe it,’ Pietro says. ‘It’s all horse feathers.’

‘If you don’t believe in fairies, you won’t see them.’

‘That’s right, Matilde! That’s exactly how things work.’

The scent of the sweet dough rising makes the girls clap their hands. Finally, there they are: the fairy cakes, perfectly golden on top.

‘They’re too beautiful to be eaten,’ Matilde says.

‘Now I understand why fairies love them so,’ Giulietta adds.

‘What are you talking about?’ Pietro says greedily. ‘I am going to have mine now.’ He snatches two and runs away, followed by his brother, who grabs two in each hand. The girls look at Bianca, who, in turn, smiles at them.

‘And now we will get the tea ready.’

She offers a cup to Innes when he peers in from the threshold, while the girls, who have been patiently waiting and couldn’t care less about the drink, savour the strange cakes with their eyes closed. They have made these treats with their own hands, and as such they have to be exquisite.

‘They are the best cakes in the whole world,’ Francesca says with her mouth full, every so often peering at the window to check for the fairies. Bianca reminds her that they need to save a few for them. Innes smiles and raises his teacup in a toast. Bianca does the same. A cup of tea really is the best thing in the whole world. It is the taste of certainty in the face of uncertainty; it’s like coming home.

‘You’re a rotten liar,’ Innes says later on, as they walk together through the open countryside.

‘Me? Why?’

‘You’ve always said you don’t like children.’

‘I don’t. Not all children. But these interest me.’

‘If only mothers and fathers thought the way you do, they would make their children quite content. But I have another theory.’

‘Let’s hear it, Signor Know-it-all.’

‘Perhaps you’re not lying. But it could very well be true, so let’s take it as the truth: you do not like children. The fact is,’ and Innes pauses to look her in the eye, forcing her to reciprocate, ‘that you, too, are still a child. And that is why they like to be in your presence.’

‘I see. And what should I do now? Pretend to be offended? Slap you?’

‘Do what you see fit, as long as you don’t act like a prim young lady. There must be some benefit to the candour of the wilderness. Can’t you see? It invites us to resemble it. It asks us to be what we truly are. What harm is there if every so often you allow yourself to be young?’

Right, what harm is there? Bianca gets up on the tips of her toes and snatches Innes’s hat from his head. She then hurls it like a disk, sending it flying through the trees before it lands in the middle of a small clearing. Innes smiles and walks off slowly to retrieve it, watched by two surprised gardeners.

At some point, Minna falls ill with a cough that won’t go away. Perhaps it is due to the changing weather or from wearing clogs with no socks. She is not allowed to go outside. Even housemaids have the right to not be well. Consequently, the duties of assisting Bianca are passed on to Pia, who is pleased to do it. She gossips, she organizes, and if Bianca asked her, the girl would crush stones and boil tinctures like a true studio apprentice. Bianca watches her eager and precise hands at work, amused and inspired. She is not at all like Minna, who is clumsy in her youth and inexperience, and who only does things to follow orders, because it is expected of her. Minna completes tasks for Bianca in the same distracted way that she plucks a duck in the kitchen or washes clothes at the well. When Bianca later asks to keep Pia as her maid, she doesn’t realize the storm that will be unleashed. In all good faith, she has imagined that for Minna one task is the same as another, a notion that, once she is better, the servant girl hastens to clarify. At first she doesn’t say anything; her silence is downright hostile. She brushes Bianca’s hair jerkily, and pulls at it like she did when she first arrived. She is so ill at ease that one clumsy gesture sends a porcelain vase of dried flowers crashing to the floor.

‘Pardon me, I’m so very sorry. I didn’t mean to.’

She bends down to pick up the shards but then drops everything again in a rage.

‘It’s all her fault I’m so worked up. It’s her fault if I break things,’ she says, crouched to the floor, her tiny face looking up.

‘Whose fault?’ Bianca asks, knowing the answer.

‘That witch. Mamma says that she tricks everyone, even ladies like you. That . . . Pia.’ She spits out her name as if it is a cuss word.

‘Oh, come now, Minna, what an awful thing to say. I thought you two were friends.’

‘Friends? I turn my back for a second and she steals my place.’ Minna is silent for a moment. She forces herself to take command of her insolence, bites her lip, takes a deep breath, but still can’t hold back. ‘She always gets what she wants. Who does she think she is? She’s no one’s daughter; she was placed in the home just like I was, but no one came back for her. She should just be quiet, that’s what my mamma says. She’s lucky she ended up in a respectable house like ours, instead of having to keep the bed warm for some bum up in Brianza.’ The venom seeps out, unstoppable. At this point Bianca is too curious to change the course of conversation. ‘Oh no, but we aren’t good enough for her. She always has to be different. Hasn’t she told you about her “lamb” and the rest of it?’ She pronounces the word ‘lamb’ with a grimace and in a strange voice, imitating her new enemy. Bianca is lost now. Minna sees that she has confused her listener. ‘Do you not know about the “lamb”?’

And from that point forward Bianca becomes truly perplexed. Minna incoherently blurts out details, complicating the picture she has already tried to paint before: the world of children given up as newborns so that parents can save money, children who are sometimes taken back and restored to thei

r regretful parents, but not always. The story has become so contorted and complicated with technical details now that Bianca has difficulty understanding.

‘She says that when they left her at the orphanage she was wearing beautiful swaddling clothes. That’s what she says. And when Don Dionisio went to get her with his sister, who weaned her so that she would be able to serve in his household and be like a daughter to her, she who had no children, he said that there was a tiny piece of paper pinned to her that said she was the daughter of a woman who had died in childbirth. He said that she was dressed in the clothes of a wealthy little girl, and that inside her bassinet she had a pledge token with a lamb on it that was embroidered in gold and silver. Of course, she couldn’t have been a poor girl like the rest of us. She had to be a princess in the orphanage, too.’

‘Wait a second. You’re going too fast, I can’t follow you. This lamb—’

‘Me, I didn’t see my pledge token, and even if I had seen it, I was too little – three days old – and I wouldn’t have remembered it. But anyway I didn’t have one. And I didn’t say I had one either. My parents were poor folk, and the poor folk don’t give pledges to children who would lose them, of course. They keep the pledges there, at the orphanage,’ Minna continues with an air of impatience. ‘They keep them safe alongside all the belongings of the other abandoned children from Milan. Pia’s pledge is a little square, about this big,’ and Minna draws an imaginary square with her tiny thumbs and index fingers. ‘The mothers put the pledges in the swaddling when they know they will come back for their children one day. Then, when they do come back, say after three years or so, they can tell the people at the orphanage: I left my baby here on such and such a day and she had a pledge that looked like this or that, and the people at the orphanage look in their books to check so that they don’t give the parents the wrong child, and if it’s all true they go and find the child, who in the meantime has gone to live in the countryside with some farmers – the fake parents, I mean. And if the child is still alive they give him back to his real parents and together they live happily ever after. Pia had a pledge with a lamb on it, but poor parents leave half a playing card, half a San Rocco devotional card, half a medallion, something that poor people have. And they hold onto the other half so that when you unite the two parts, it makes up the whole, and that means you get the right baby. Your baby. Do you understand?’ Minna is silent now. She is out of breath and her face is flushed. She stands up, the shards of the porcelain vase crackling under her clogs, but she doesn’t notice. ‘Anyway, the truth is, no one wanted her back, so it’s about time that she stopped showing off and learned her place, and that’s that. And with that, I pay my respects and wish you a good night.’ Minna stomps off with tiny, angry steps, leaving behind a cloud of confusion.

Bianca feels disconcerted. What is all this nonsense about abandonment and recovery, beautiful swaddling lambs and pledges? Aren’t two abandoned girls under one roof too many? Or is it normal around here to just dispose of your burdensome children? What does Don Dionisio have to do with anything? Perhaps Minna is just stringing together bits of gossip she has overheard in the kitchen, embellishing them with spite and fantasy. It is surely just childish confusion, a joke born of jealousy, something that happens downstairs in every large household. Minna is a good girl really. She will get over it. She’ll probably even feel sorry about what she’s said. But Bianca also realizes that Minna knows how to find the right words, even complicated ones, despite being red with rage. She has been under the impression that the girl is accustomed to getting distracted and lost in thought, but not this time. The little girl has spoken and heard this speech many times and it clearly always leaves a bad taste in her mouth.

Bianca tries to think about other things but in vain. She feels irritated with herself for not being able to soothe Minna’s spite. She replays the girl’s monologue inside her head, trying to make sense of all that scattered information. And then, all of a sudden, she remembers the little pillow she found. She opens the drawer of her nightstand and, pulling out that odd square she’d found on her walk in the woods, she thinks back to Minna’s words.

Pia’s pledge is a little square, about this big . . . The mothers put the pledges in the swaddling when they know they will come back for their children one day.

Bianca isn’t sure if this is a pledge because she has never seen one. Neither has Minna really, so she can’t ask her. But if it is, what was it doing lying in the grass without a child? Or maybe – could it be that somebody has abandoned a newborn in the woods and left the token behind? No, it cannot be. She would have heard rumours about it, and the child most likely would have been torn to pieces by wolves. Don’t be foolish, Bianca tells herself, trying to repress the absurd thoughts that crowd her head. And yet she continues to rack her brain, unsettled and intrigued. This is better than a novel. This is real. That odd pillow embroidered with so much care actually exists – and it has to mean something. Bianca decides she will take it upon herself to discover what that meaning is.

The rivalry continues. Pia and Minna don’t talk to each other. The little one is steadfast, obstinate, and convinced that she has been subjected to an unforgivable wrong. Pia shrugs and calls the other girl crazy, but Bianca can see how sorry she is, how she torments herself to make the situation right again. Bianca, who feels guilty for having unleashed the dispute, finally finds a remedy after explaining the situation to Donna Clara.

‘A conflict, you say? Why on earth, when we treat them so well?’

Yes, Bianca thinks to herself, like little animals in a cage.

‘You know how young people are: they have their tantrums, their little fights.’

She thinks minimizing the situation is the best way to achieve her goal. She makes an offer. At first Donna Clara seems a little uneasy and looks at her with suspicion: is Bianca, a stranger, trying to lay down the law in her own home? Who cares about the housemaids’ bickering? And yet, it is clear that she feels a special kind of love for those girls and wants justice and harmony on her land. Bianca understands all of this.

‘Very well. Just keep me informed. What little scoundrels they are! We give them everything: clothes and shoes, warmth and food.’

Bianca cannot help but comment.

‘I suppose you’re right. Once man’s primary needs are met, other aspirations are awakened. It is inevitable.’

Donna Clara looks at her with a scowl. She won’t let herself be taken for a fool.

‘You are a true intellectual, Miss Bianca. Ah, women with brains . . .’

And with that, the rotating shifts begin. One day it is Minna’s turn, the next Pia’s. Sometimes both of them divide the tasks: the one who brushes Bianca’s hair doesn’t accompany her, and vice versa. When Bianca tells them of her new plan, they listen to her in silence. Minna is stubborn, retaining her identity as the violated one. Pia, on the other hand, is pleased. And it is she who holds her hand out to the other.

‘Can we make peace?’

Minna glances at Pia with her outstretched hand, and stares at a point in the sky in front of her. Then she giggles, shrugs her shoulders, and lets herself be hugged. Bianca gazes from one girl to the other, amazed at how different they are despite being raised under the same roof. The little one is contentious and a trickster, with a sharp tongue and a sly mind. The older one is generous, willing to give up some ground for the love of peace. It is useless for Bianca to play favourites. But perhaps Minna will change, if guided appropriately. She hopes that Pia, on the other hand, will never change: she is beautiful and sincere, somewhat vulnerable perhaps, but only inasmuch as the other is armed, and nonetheless strong in her simplicity, keeping her one step ahead of the game.

The following Monday it rains again but this time Bianca can no longer resist. She takes down a rain cloak from the coat rack outside the kitchen and walks out. It takes only three steps for her to regret making the decision: all kinds of smells linger on the oilcloth fabric – dog, gravy

from a roast, ash. An overall film of dirt that has come to life, thanks to the humidity in the air. It isn’t very pleasant being enveloped by such intense smells; they suffocate the wonderful scents of the wet park. But it is too late to go back now and besides, Ruggiero’s cloak does the job: the drops of rain roll right off it.

Her sixth sense has been right. The ghost is there. But this time she has pinned her veil up to her hat. She moves forward through the tall grass slowly, holding her skirt with both her hands. She stares into the distance. Even from far away, Bianca can see her large eyes and pale skin. Her pace is long and elegant. Bianca is ready to approach her. She isn’t far. She will find out for certain who she is. But then she freezes suddenly, overcome by a wave of dread as well as respect. The lady stops, lowers her head, and stands as still as a statue. A sudden gust of wind blows the veil over her face. Now she is frightening, and truly ghoulish. Bianca turns around and darts back to the gate, which she has left ajar. She closes it behind her, turns the key in the lock, and takes it. And then runs as fast as she can.

She sketches her vision that same night so as not to forget any details. That veil, embroidered with small droplets, is like a bride’s, fit for a fairy-tale princess. The woman’s eyes are large and deep, even behind the grey material. She has a generous mouth, a determined nose and an imperious chin. Bianca is certain that she will be back.

But, in fact, she never returns. She isn’t there at the vespers hour the following Monday, Tuesday or Thursday. Her absence does not go unnoticed. Even the help gossip about it.

‘She’s not coming back.’

‘Her soul must have finally found peace, poor thing.’

‘Maybe she died of the flu.’

When Bianca asks around for more information, the women hush, look at one another, and change the topic. Apparently, since she has stopped coming, she no longer exists. Soon there will be another curiosity to serve as the topic of discussion while plucking quails. Like old Angelina’s son, for example, who won’t stop growing: he is twenty and looks and eats like an ogre. Or the button seller, who has the eyes of a gypsy: they say he robs virgins of their souls, or something easier to come by.

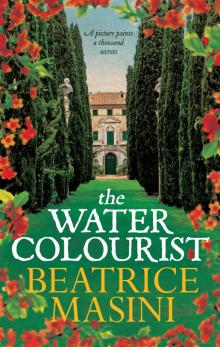

The Watercolourist

The Watercolourist